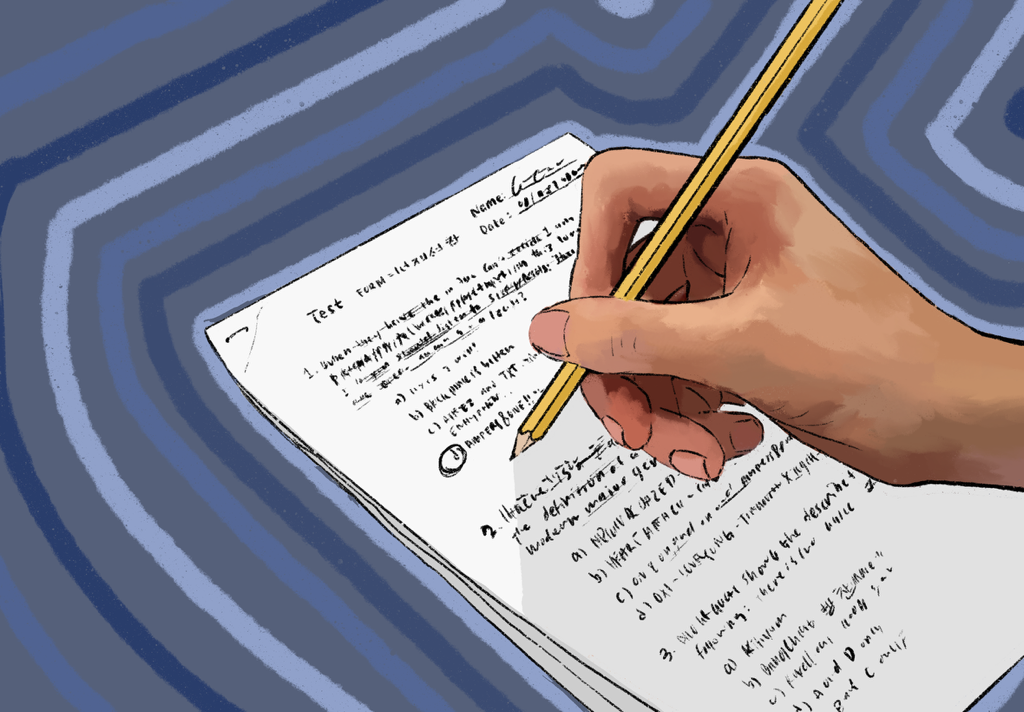

Counterclockwise from top right: Katharine Li’s ’17 entries to the Choate Gingerbread House Competition in 2013, 2014, and 2015.

Take it from a three-year (not four-year, tragically) Choate Gingerbread House Competition champion: to become a maker of gingerbread houses is no joke. It’s a calling. Just Google “First Lady Laura Bush gingerbread White House.” You’ll see.

I can understand why some people devote huge amounts of time to the practice of gingerbread architecture. Forget palettes of weird-smelling paint and non-edible embellishments; imagine spending your life exploring Van Gogh and Martha Stewart’s scrumptious lovechild. And if you eat your product, it’s not even considered cannibalism. Who wouldn’t give it a try?

Apparently, not a lot of Choate kids. Three years ago, the smell of sugar and spice was not enough to entice my peers at Choate into trying the craft. My freshman year, most student participants in the gingerbread house competition were in it for the $10 Walmart gift card that came with signing up. A group of boys in Memorial House ran out of icing and presented a finished product that had used shaving cream instead. To most, the gingerbread house competition was just another casual, ultimately forgettable campus event.

But something about being an architect of an edible house stimulated my artistic and foodie inner selves. I knew that if I were to make a gingerbread house, it would be more than a fun weekend project. It didn’t matter that none of my competitors were taking the contest seriously. I was going to go big or go home. And go big, I did.

For the weeks leading up to the competition, preparation for the gingerbread house competition consumed my life. My head was bursting with ideas for what I would create with gingerbread, icing, and ten dollars for candy decorations. I looked to my prefects and dorm mates for support. They slaved away with me for the whole week leading up to the competition (a privilege of being a freshman with actual free time). In the Squire common room, our a giant Victorian edible castle, one destined to blow the judges away, was born.

Through a snowstorm, like Brave Irene, I and my team carried the creation to the dining hall for judging. As we walked underneath the moose, the seniors greeted us with applause. In that moment, I forgot all about the icing stains on the common room carpet that I knew my adviser would later berate me for. Everyone was looking at our gingerbread house, and everyone was amazed.

Building that year’s gingerbread house was my first exposure to what would become, for me, an essential part of the holiday season at Choate. My sophomore year, I created a Japanese pagoda with my roommate in our room in Bernhard House. Junior year was the Grand Budapest Hotel, decorated while propped on the table in Library dorm’s common room. I learned a few maxims along the way: $10 was nowhere near enough to create an extraordinary gingerbread house; cleanup was always a pain in the neck; making Mr. Yanelli smile was even better than being the centerpiece of Holiday Ball.

Tragically, it all fell apart this year. Yes, my gingerbread house collapsed halfway through its assembly, and at 1:00 a.m., shocked and blearly-eyed in the Bungalow’s quad, I couldn’t muster the energy to finish strong. The remnants of an edible Taj Mahal that would never be lay before me, blue and white icing smeared into my room’s carpet. Am I ashamed that I let my fans down? Yeah. Would I have like to won the competition for four consecutive years? You bet. But I reckon part of being a senior is recognizing that your time is nearing its end. I know it’s now up to the underclassmen to continue my legacy, and I’m sure there’s someone out there who can do it. Are you reading this? Remember: nobody ever actually eats the gingerbread, and anything is edible if you try hard enough.