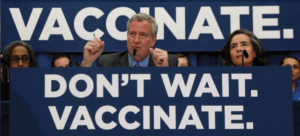

On April 9, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio declared a public health emergency and mandatory measles vaccinations in response to an outbreak among ultra-Orthodox Jews in Brooklyn. Photo courtesy of Reuters

The recent measles outbreak in the United States has defied norms. The disease, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention declared eliminated in 2000, has resurfaced in recent years, with the number of reported cases rising from 120 in 2017 to 372 in 2018. In just the first four months of this year, 465 cases have been reported.

The outbreak has largely been attributed to vaccine hesitancy: the reluctance or refusal to vaccinate one’s self or one’s children even in light of accessible immunizations. Vaccine hesitancy was listed as a top ten global health threat of 2019 by the World Health Organization (WHO), and is usually rooted in reservations about vaccine safety and health effects, often with little to no scientific evidence to support such fears.

People who have not been immunized pose a threat to those who are unable to get vaccinated because of weaker or compromised immune systems. For example, most infants are not vaccinated against measles until they are 12 months old, but they are protected from measles exposure by the immunity of adults around them, which prevents the disease from spreading.

Other people, including the elderly, cancer patients with immune system problems, and others with immune deficiency disorders are also put at risk every time someone who could otherwise safely get vaccinated chooses not to do so. Clearly, if you are healthy enough to get vaccinated, you ought to, but misleading studies and a strong internet community fostering cognitive dissonance and rejection of evidence have led many people, especially parents, to reject the overwhelming benefits of an immunized society in favor of protecting their children from a danger that isn’t really there.

Historically, vaccines have been mandated for all children attending public school unless an exemption is granted. All fifty states offer a medical exemption, 47 offer a religious exemption, and 17 a philosophical exemption. A major step in restraining the current measles epidemic would be for states to limit these exemptions as much as possible. Our society does allow for free thought and expression, but if those ideas are putting others in danger, then something must be done to protect those who are at risk. In this case, vaccine hesitancy is being used as a justification for an exemption. Anti-vaxxers argue that government mandated vaccination, at least in order to enter public schools, would be a violation of personal freedoms. Here, however, the government would be creating a safer society.

Although the religious exemption has generally been supported by the general public and vaccination legislation, the recent outbreak has brought the issue up for debate. The exemption is designed to allow members of religious groups such as Amish communities to preserve their religious beliefs and remain unvaccinated. However, many have recently called attention to the repercussions of the religious exemption.

The recent measles outbreak has largely afflicted Orthodox Jewish communities, and the disease was reportedly brought from Israel, where ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities are currently experiencing a similar outbreak. However, leading rabbis in Jewish communities have stated that vaccination does not violate Jewish law, and that the recent outbreak can actually be attributed to anti-vaccination misinformation being spread within these isolated orthodox communities. This is the consequence of allowing people to spread false ideas. Anti-vaxxers have put an isolated community at risk by exploiting its disconnection from the rest of society.

The debate over mandatory vaccination will come down to whether governments and societies at large decide whether or not public health and well-being justify potential infringements of personal freedom.With the levels of misinformation being spread and the danger that preventable diseases pose to society, states must take action to ensure that as many people get vaccinated as possible.

There is no reason for a developed nation like the United States to take the gift of vaccines for granted. Many developing countries have yet to see widespread vaccination; a 2017 report found that 64 of 195 countries have failed to meet a basic vaccination target set by WHO. These countries would benefit greatly from a resource that some Americans feel is unnecessary or even harmful. Measles, polio, HPV, pertussis, and the numerous other diseases that vaccination have helped limit are dangerous and must be taken seriously. Ignoring technology that has saved lives for generations is both selfish and ignorant, and states must take action to curb this public health threat.