Tackling the gender disparities in STEM has long been a topic of interest at Choate and beyond, but the spotlight on gender inequality in the social sciences has not shined as bright. Many Choate students, regardless of their gender identity, have felt the impact of a gender imbalance in classrooms and the club life of social science disciplines like economics, government, and psychology — fields that men typically dominate.

For many female students, it can be discouraging to pursue interests in these male-dominated areas. Alicia Xiong ’21 has long been interested in economics. She said, “I think that girls feel uncomfortable with economics itself. Frequently, we are told to stay away from STEM fields, and economics does somewhat fall under this category since it requires a strong background in math. As a result, we see fewer females represented in those fields and even fewer in power.” Indeed, according to the American Economic Association, just 33% of American doctoral students studying economics are women, and only one woman, Janet Yellen, has ever served as the chair of the Federal Reserve.

This attitude carries over into social sciences-related Signature Programs. Although the John F. Kennedy Program in Government and Public Service intentionally selects a near-equal number of male and female students regardless of the breakdown of its applicant pool, Rory Latham ’21, a member of the JFK program, noted that “people are more surprised when a girl says she’s in JFK than when a guy does, based on some cultural expectation that politics, at least at Choate, is male-dominated.” In fact, 35 female students and 30 male students, along with one nonbinary student, have been offered spots in the JFK program over the four years it has existed.

This culture of exclusion seems to also carry into social science-oriented extracurriculars. In a project on the gender dynamics of Choate’s club life that she completed in the winter term for her women’s studies class, Charlotte Myers-Elkins ’22 “traced [the male-dominated speaking time of many clubs] to the environment of mansplaining, talking over girls, discouraging them, and making them feel less confident in their answers.”

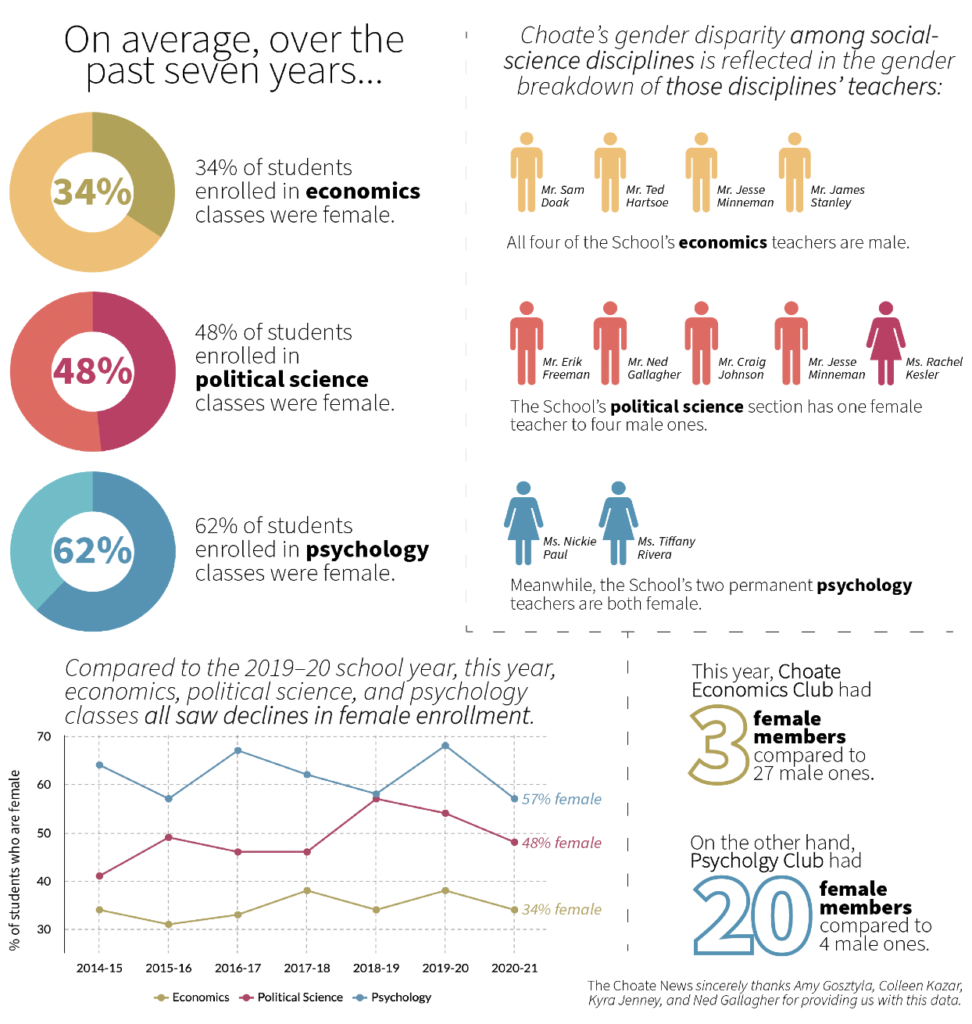

For the 2020-2021 academic year, the majority of social science clubs at Choate, such as Economics Club, Young Republicans, and Choate Finance and Investment, reported more male members than female, with the exceptions of Young Democrats, which this year counted 41 female members to 38 male ones, and Psychology Club, which counted 20 female members to just four male ones.

The Choate Economics Club reported an especially drastic gender disparity, with 27 male members to just three female ones. Xiong, a former cabinet member of the club, believes there is a connection between the disparities that exist in club life and in the classroom. She said, “It is saddening to see this gender disparity exist in the club, and I think part of that stems from the academic side of economics, which is also male-dominated. Our club has struggled with trying to increase female participation.”

But, even clubs whose memberships are relatively balanced between genders, such as Young Democrats, aren’t immune to these issues. Latham, a former president of Young Democrats, noted that the club sees “more regular male speakers, and I think that could discourage women who would otherwise speak up, seeing a couple guys talk for a few minutes straight and at least seem like they know a lot about the topic. It might discourage someone who knows just as much but doesn’t have the same confidence or support to speak up.”

Instead of feeling uncomfortable fighting for speaking time in male-dominated club environments, some female students choose a different path: female-oriented affinity spaces. Myers-Elkins, the president of Choate Women in Business, explained, “Because women are discouraged from going to these clubs like Choate Finance Club, they try to find a more supportive environment where they’re able to pursue that passion, and that’s typically in clubs with the word ‘women’ or ‘girl’ in it.”

In spite of these affinity groups, the widespread attitude and discomfort in club life has, to some degree, fed back into the enrollment patterns that drive female students away from economics classes. Myers-Elkins said, “Girls are kind of discouraged from taking higher-level economics classes at Choate, and a lot of it has to do with the confidence they feel when entering a club environment where they’ve been made to feel less educated in a specific topic.” This year, nearly twice as many males as females took an economics class at Choate. Still, at 51 females (to 98 males), that’s the highest number of female economics students since 2012, when records began to be kept.

As HPRSS Department Head, Ms. Kyra Jenney pointed out that female students are certainly interested in economics classes, and “the introductory courses don’t necessarily have a gender imbalance.” Unfortunately, she continued, “I think that probably becomes less so the case as you advance along in the discipline, and when you get to some of the higher courses, whether that’s advanced topics, monetary theory, or international economics. That’s where we’re starting to see more of the gender imbalance crop up, where there are fewer young women continuing past those introductory courses.”

Indeed, for some students, it is their experience inside the classroom that stops them from pursuing more advanced classes in a particular discipline. “At least for me, I don’t like to be in a male-dominated classroom because I tend to shrink back in conversation,” said Xiong.

One critical issue that students and teachers alike point to is the issue of representation within the classroom. Noticeably, all of Choate’s economics teachers are white and male — a disparity that seems all but guaranteed to affect the class environment and students’ experiences, especially those of women and students of color. In contrast, the psychology teachers are all women and include a woman of color. As it happens, Psychology Club’s roster is over 80% female, and this year, 56 females took a psychology class, compared with 43 males in those classes.

“When you see someone who looks like you, who has gone that far in the discipline, [and] who has made a career in that discipline, it tells you, even subconsciously, something about the nature of that discipline,” said Ms. Jenney. “If you only have female psychology teachers, you’re getting the message, even subliminally, that to advance in that discipline, to become an expert in that discipline, and a teacher within that discipline — that’s what you have to be.”

Of course, there are reasons for these gender imbalances within the social sciences that expand far beyond Choate’s classrooms and clubs. Because the social sciences are male-dominated, broader attitudes of sexism inevitably permeate the Choate campus. Ms. Jenney said, “Choate is not immune from larger cultural, social, political, and historical phenomenon, so all of the gender dynamics, imbalances, institutionalized sexism and misogyny that you see in the world more broadly, whether that’s in business, government, politics, or wherever, Choate is going to reflect that to some degree as well.”

To the same effect, Assistant Director of Student Activities Ms. Colleen Kazar added, “I think students are exposed to what the population of gender within those careers is, so people generally tend to flock towards something where they see somebody who looks like them in terms of gender identity.”

Still, despite this broader culture, community members are committed to chipping away the male-dominated status quo on campus. “We’re in a position to take note of [these gender disparities] and push back on them because we’re in charge of this institution,” Ms. Jenney said.

For example, the HPRSS department uses the JFK program to promote equality in the social sciences. The program, whose selection committee strives to be “mindful of overall issues of representation,” according to program director Mr. Ned Gallagher, has selected more female students than male students since its founding in 2018. The program’s participants are then required to take both introductory and advanced courses in political science and economics, which has helped boost female presence in these disciplines.

Ms. Jenney concluded, “It can’t stop just with listening and learning. There also needs to be tangible action to push our community forward.”