With Black History Month well underway, many local groups and organizations are remembering Connecticut’s Black communities’ rich histories. Sites important to Black history exist across the state, from historical museums and the first boarding school for women of color, to the birthplaces of famous abolitionists.

John Brown Birthplace Site

On John Brown Road in the western part of Torrington is a 40-acre site where abolitionist John Brown was born. Although the house, which was owned by Brown’s father Owen Brown, was destroyed in a fire in 1917, the property and the granite monument laid in 1932 to commemorate the birthplace are currently maintained by the Torrington Historical Society.

In addition to his involvement with the Underground Railroad, Brown led the Harpers Ferry Raid in 1859, as an effort to start an armed revolt of enslaved people in the South by overtaking a United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The event has since been recognized as a precursor to the Civil Rights Movement in America.

The Torrington Historical Society’s Executive Director Mr. Mark McEachern said, “John Brown was a rare abolitionist because he believed in racial equality that many abolitionists who wanted to end slavery did not. He formed alliances with Black people and he invited them into his home and shared his dinner table with them.” Mr. McEachern believes that the historical site is equally important in its association with John Brown’s father, Owen Brown, who was also an abolitionist and inspiration to his son. Owen Brown was one of the founders of numerous abolitionist societies in Ohio, such as the Western Reserve Anti-Slavery Society, as well as the Western Reserve College, an abolition-oriented institution of learning.

To educate people about the life and times of John Brown, the Torrington Historical Society is currently in the process of planning and constructing an interpretive trail around the property that will consist of a series of historical markers. The society’s other efforts include actively collecting information related to Black people who lived in Torrington, as well as planning programs and social media posts on Black history, including posts on John Brown and his commitment to civil rights.

In regards to the society’s interest in not only Brown but also the Black people he collaborated with, Mr. McEarchern said, “It’s important because we’re all Americans, and it’s important to advance the cause of equality and civil rights and celebrating Black history helps that.”

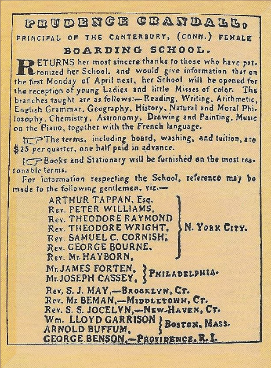

Prudence Crandall Museum

Situated at the site of the first-ever boarding school for young Black women in the United States, the Prudence Crandall Museum is a National Historic Landmark and State Archeological Preserve located in Canterbury, Connecticut.

In 1831, Prudence Crandall opened a private academy for white students in Canterbury and neighboring communities. When Crandall accepted Sarris Harris, the sister-in-law of the household assistant, into the school as the first Black student, the white families threatened her by pulling their daughters out of the academy. Crandall then reopened the school exclusively for “young ladies and little misses of color,” with Black women and girls coming from all over New York City, Rhode Island, Philadelphia, and Connecticut to study.

“She taught them a rigorous curriculum with courses ranging from astronomy to moral philosophy that most of these African American women would not have access to otherwise,” the Museum’s curator, Ms. Joan DiMartino said. During the Academy’s 17 months of operation, Crandall was imprisoned for one night and forced to participate in the court case Crandall v. State as a consequence for breaking the “Black Law,” which prohibited bringing Black people into the state of Connecticut for education.

After enduring continued harassment, increasing violence, and, ultimately, a mob attack on the school building in 1834, Crandall decided to close the Academy for the safety of her students. “A lot of people will say the school was a failure because it closed down due to violence, but I would argue that the school was quite a success because these young women that attended the schools went on to do amazing and important things in life,” said Ms. DiMartino.

Take, for instance, Mary Myles Bibb, who, with the help of her husband, started a newspaper called the “Voice of the Fugitive,” which focused on the issues of education, moral elevation, and freedom for newly arrived, fugitive enslaved peoples in Canada. The Bibbs also helped found the last stop on the Underground Railroad, aiding the self-emancipated Black people who fled slavery and escaped to Canada to buy land and begin their lives as free people.

In awe of the successes accomplished by these students, Ms. DiMartino said, “I hope people will come in and visit us sometime in the future because it’s amazing to be in this space and walk the floors that these women walked on.”

She added, “My perspective here is that Black history does not begin and end in February. It is part of the national fabric of our nation and that we should just be talking about it all the time.”

In the coming years, instead of opening the Museum for only half a year, Ms. DiMartino hopes to continue sharing the story of the Prudence Crandall museum with visitors all year long — after a renovation of the property has been completed.